Smart city infrastructure that is capable of pulling data from multiple sources is ideal. However, cities can benefit from smart city solutions.

“Smart city” brings to mind a futuristic city packed with technology, but they are already here. Many people are aware that cities take advantage of early warning systems (EWS) to alert city managers of potential tsunamis and storms through the use of data analyzed by artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms. Few are aware some cities are so smart that AI programs are running seamlessly without the average citizen noticing. For example, Las Vegas uses Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as cameras connected to the Internet to collect and analyze traffic data in real-time to predict potential car crashes and alerts local authorities to take preventative measures. In India, the Prayagraj Smart City Mission team prevents stampeding deaths during certain festivals with a crowd management application (CMA) system which calculates crowd density. The system uses 700 closed camera television (CCTV) feeds to monitor how many people are in one spot and flag security forces when they need to intervene. The monitoring is invisible to the 250 million festivalgoers at the annual Magh Mela festival, yet the control center resembles Cape Canaveral’s Launch Control Center. I believe smart cities with IoT solutions can be found across the planet, although there is little consensus on what constitutes a smart city.

“Smart” cities used to refer exclusively to connecting city infrastructure services to the Internet to track different aspects of the cities ranging from traffic to energy grids, a practice many refer to as the “Internet of Things” (IoT). The rise of AI in recent years led to the term “Digital Cities” in reference to how cities aggregate and analyze data to help guide and execute citywide actions. Since both terms relate to data, the terms “smart city” and “digital city” are often used interchangeably, which leads to confusion. It makes sense to refer to “digital cities” when referring to the data itself and how to best store, manage, analyze, and execute actions based on the data. These digital cities do not necessarily require a centralized infrastructure to work and, in such cases, are not smart cities. The definition is further complicated when many refer to cities where many smart applications operate a myriad of services such as finding parking spaces, tracking buses, and showing locals and tourists crowdsourced crime data as “smart cities.” The question is thus: what makes a city “smart”? One may argue that a collection of smart apps does not constitute a smart city. A smart city is composed of infrastructure that supplies city managers, businesspeople, and residents with the ability to connect systems to make the city safer, more efficient, and/or deliver a better quality of life.

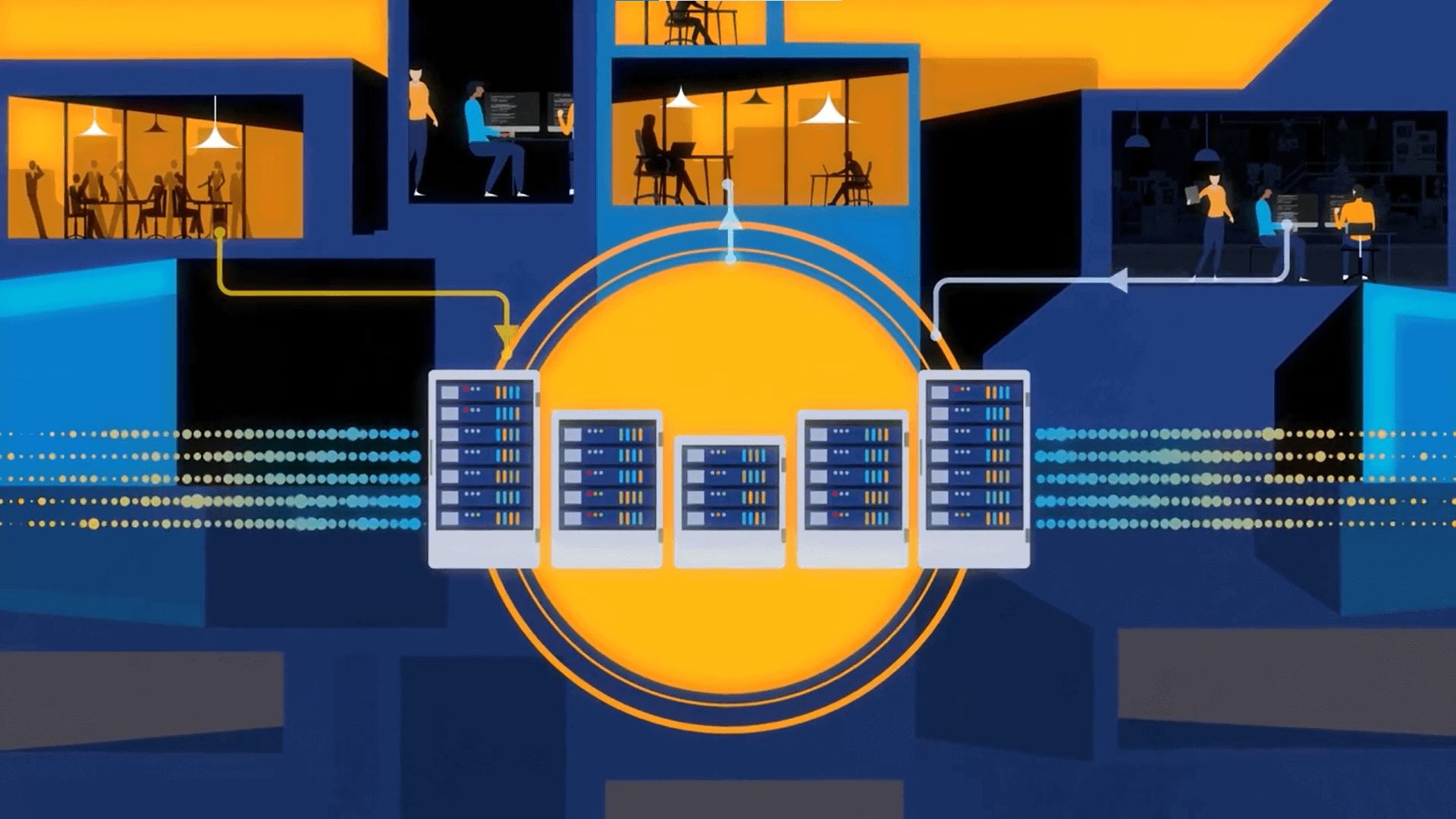

Many cities recognize that to be smart, different systems and data need to be part of an infrastructure. These cities either develop their own digital infrastructure or acquire an infrastructure from another organization. For example, FIWARE offers a standardized smart city operating system (OS) that facilitates interaction between IoT sensors and other devices. It processes stored and real-time data and creates dashboards to monitor what happens in the city in real-time. Many cities employ proprietary platforms such as Cisco’s Kinetic for Cities platform, which also aggregates real-time data from multiple IoT sensors and other devices for city leaders. The cities that rely on Cisco’s platform have a problem, however: Cisco stopped selling the platform in 2020 and announced it will end support in 2024. Cities such as the American city of Las Vegas, the English city of Hull, the Indian city of Jaipur, the American city of Syracuse, and the Danish city of Copenhagen, will need to either find a replacement or maintain the platform on their own. This illustrates the need for flexibility to ensure the cities’ capabilities can grow and be maintained regardless of the fate of companies that contract with the cities.

Smart city infrastructure that is capable of pulling data from multiple sources is ideal. However, cities can benefit from smart city solutions. Cities can solve urban problems through the use of IoT applications. The apps are not smart city infrastructure; the apps better resemble the vehicles that drive on roads. The infrastructure of a smart city is what allows the apps to work. In terms of a parking app, the “infrastructure” would be the network used to transmit information about whether a parking space is filled. If a smart city wants to hasten the development of smart cities, it can focus on building open standards and soliciting proposals for specific smart city solutions. For instance, according to a 2018 report, different Croatian cities sponsored workshops and hackathons to address each city’s needs and interests. Zagreb hosted competitions to create smart solutions in the tourism industry, and Dubrovnik hosted hackathons that led to the creation of projects such as the Smart Sprinklers irrigation project, which uses infrared parking sensors to aid in smart parking, and sets the stage for large scale traffic monitoring. According to a report, more than 40 of Croatia’s 128 cities use smart city solutions. These examples illustrate the importance of smart city solutions being of benefit to cities. Furthermore, the rise of smart applications can be strengthened by the use of open standards, which provides a common basis to facilitate the creation of the applications.

The question is: if you can make a city with smart city solutions, why should one make a smart city? Infrastructure would facilitate the creation of more smart city solutions by giving app developers easy access to vast amounts of data and a common way of accessing such data, which could make it easier for apps to talk to each other. The use of a single source of information system also avoids confusion when data is available from many sources and may contradict each other. For example, Google Maps sources its bus schedule data from public bus schedules while apps such as Transit use the GPS coordinates from the vehicles themselves, and the data sometimes conflict. If the purpose of smart city solutions is to make peoples’ lives better, than the creation of smart cities is vital regardless of the definition.